"We invariably charged right in their midst, and confused them, and had them miss me more than once at no greater distance than 10 feet, whereas they could hit a man every time at 60 yards when not tinder excitement."

As expressed in his Autobiography, this could be called the George Crook Philosophy of Indian Fighting. Although there was nothing new about the tactic of aggressive attack, Crook felt that it was ignored by many of his garrison-lazy contemporaries. When left to his own devices along the Pit River in 1857, Crook put action to the words.

The system was not 100 per cent foolproof, Crook found, but perhaps his personal case was the exception to prove the rule. He was one of the first casualties on the Pit River Expedition, taking a poisoned arrow in the right hip. He was laid up for more than two weeks until the poison had dissipated. The arrowhead never was removed.

While he was recuperating at a field camp along the Fall River, Crook was joined by Captain John W. T. Gardiner, 1st Dragoons. Gardiner had orders to take his Company A to the vicinity of the Pit and Fall Rivers and establish a post. As usual, the orders added, "Temporary quarters and stables only will be erected at the post."

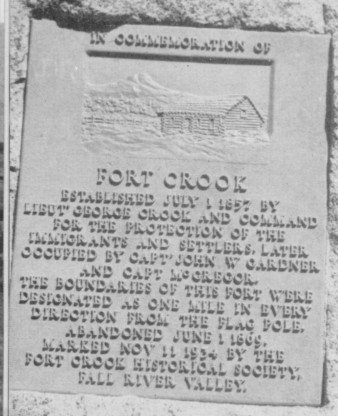

Gardiner's first inclination was to name his new post Camp Hollenbush, after his company's surgeon. On July 1, 1857 be settled on honoring his surgeon's most redoubtable patient, George Crook. By this time the fort's namesake was busily demonstrating the worth of his Indian fighting theories.

Problems for both officers came from a new direction, that of Fort Jones and the officer least admired by Crook: Captain Henry B. Judah. It was only through the sufferance of Judah that Crook and a detachment of 25 infantrymen were in the Pit River Valley. Judah decided that be wanted Crook and company back at Fort Jones, and on July 11 be made his stand in no uncertain terms. Gardiner was accused of gross disrespect and Crook was threatened with a court-martial if he did not return at once.

Something caused Judah's temper to cool. Crook was permitted to remain, perhaps because Judah remembered that be never got along with Crook, anyway.

The absence of affection between the two officers had to do with Crook being alone in Pit River country at a time when it was subject to Indian terror. The force originally included both Company's D and E, 4th Infantry, for a total of 65 men under Captain Judah and First Lieutenant Crook. The expedition was to visit the scene of a wintertime massacre and, if possible, run down the culprits.

As Crook's Autobiography notes, the affair started badly. "It was as good as a circus to see us when we left Fort Jones," he wrote. "Both companies were mounted on mules, with improvised rigging, some with ropes, and other with equally, if not worse, makeshifts to fasten the saddles on the mules, and all did not have cruppers . . . Many of our men were drunk, including our commander. Many of the mules were wild, and bad not been accustomed to being ridden, while the soldiers generally were poor riders. The air was full of soldiers after the command was given to mount, and for the next two days stragglers were still overtaking the command."

Comedy did not stop when the hangovers passed, according to Crook. Several days later, Judah led the troops in a wild charge against an Indian village that Crook insisted was abandoned.

"It was as good as a circus to look back over the field be crossed to see the men 'hors-de-combat,' riderless mules running in all directions, men coming, limping, some with their guns, but others carrying their saddles," said Crook in the Autobiography.

As far as Judah was concerned, that was the close of the expedition. "Capt. Judah had just been married the second time," Crook explained, "and was anxious to get back to his bride. Soon after getting back to our old camp, he returned to Fort Jones, leaving me with only 16 men of my company to accomplish what he failed to do with his two companies. He reported upon his return to Fort Jones that there were no Indians in the country, etc. etc."

Left alone with his 16 men, or the 25 noted in the official orders, Crook "knew that there were plenty of Indians, and that my only show was to find where the Indians were, without their knowledge, and to attack them by surprise."

Assuming that Judah's departure with most of the troops was noted by the Indians and that "they would be off their guard," Crook took two men and scouted the area. After finding a rancheria, he tried to take his larger force on a night scout to it, but "by some mistake we became separated." An attempt to do the same the next night was successful, except that the Indians had disappeared.

Crook and Dick Pugh, a civilian guide who served Fort Crook for most of its 12 years, patrolled continually. On one occasion, Crook chased several Indians and killed one, then bad to turn tail with the Indians in hot pursuit. "A big Indian, seemed to me about 10 feet high, was running his best to catch up . . . his arrows flew around me with such a velocity that they did not appear over a couple of inches long."

Later the same day Crook's command was attacked while in a box canyon. This was the occasion of his wounding and its announcement at Fort Jones resulted in the whole command being ordered out. "As usual they got drunk, Judah included, who fell by the wayside," Crook commented, but a doctor "with all the available men came out."

After returning to duty, Crook continued his aggressive pursuit of the Indians. On July 2 and again on July 27 his command clashed with the Indians. The former was a hand-to-hand fight "so close we could see the whites of each other's eyes."

After peace came, "it became irksome and monotonous to be lying around camp," so Crook spent his time on hunting trips to supply fresh meat. Gardiner's troops were concentrated to such an extent on building the fort that two years later Inspector General Joseph Mansfield could blame their military deficiencies on the fact "they have been laborers and mechanics, building log houses, etc., for the past two years."

When Mansfield visited the post, be found it manned by companies A and F, 1st Dragoons, for a total present of three officers, one assistant surgeon, G. C. Hollenbush after whom the post was named for a few days, and 103 enlisted men.

Mansfield was especially critical of First Lieutenant Milton T. Carr, the acting commander of Company A and the quartermaster and commissary officer at the post. The combination of three duties was not happy. Mansfield found that none of Carr's accounts was handled properly, from the $1,542.62 on the company's books that had not been balanced and were "handed to me the evening before I left," to Carr's writing a check for the commissary department "in expectation that a deposit would be made in time to meet it."

Apparently Mansfield was impressed with the fact that Carr could spread himself between three jobs. Still be reported officially, and probably kindly, "I do not think Lt. Carr had a taste for accounts, and in addition, he has too much duty to perform."

Mansfield was impressed with Fort Crook. "This post is well located to overawe the Indians and protect the emigrants transportation travel between the eastern states and California, and should be maintained and garrisoned with not less than two companies," be reported.

His report recited a "number of murders which have come to light" including five in 1851, five in 1856, six in 1857, two in 1859, and plus considerable looting and animal theft. The stage line also was attacked with the driver escaping after he cut loose his horses "with many arrows shot into him."

The situation improved somewhat during the Civil War although frequently the post was reduced to 25 men. Officially it had two companies of the 2d Cavalry California Volunteers, but the need to place outposts placed a strain on its manpower. The frequent expeditions, usually to settle friction between white man and the local Native Americans, kept the post at minimum strength.

William H. Brewer stopped at Fort Crook in 1863 when most of the garrison were Indian chasing. "Lieutenant Davis, in charge of the post, was very kind and gave us hay for our horses," Brewer wrote in his diary. "Except for 10 or a dozen men the troops are all away now, fighting Indians. It must be a lazy life, indeed, in such a place."

Captain, later Major, Henry B. Mellen, commander of Fort Crook through most of the Civil War, effectively carried on its peace keeping mission. "My constant policy has been to treat the Indians justly, and to impress them with the idea that while I will severely punish them when guilty, I will protect them if they keep good faith and are peaceable," be announced,

After several instances of Mellen vigorously defending the rights of the Indians, the local tribes were convinced. Aware that Mellen was fair to both sides, one tribe refused to harbor an Indian renegade who was being hunted for robbery and several three-year old murders. "Fearing that by his acts be would get them into trouble," the tribe surrendered the fugitive. Mellen had him shot. "The tribe express themselves as satisfied with the justice of the sentence."

Fort Crook lasted throughout the Civil War. At the end of the war, it was listed as one of the few camps that should remain for at least "the present winter," When winter ended in 1866, so did the history of Fort Crook as the troops were moved to newly constructed Fort Bidwell in the far northeastern corner of California.

TO GET THERE: From Redding, California (where Fort Reading was the post replaced by Fort Crook), take State 299 about 70 miles northeast to Fall River Mills. Turn left (north) on Farm Road 1220 to Glenburn, 6 miles. At Glenburn post office, turn left (north) on road A19, follow it around 3.2 miles to marker next to fort site.

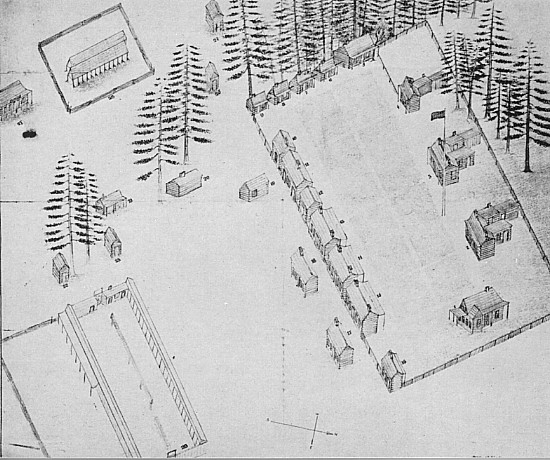

The Civil War appearance of Fort Crook was sketched by Private F. Selby, Company C, 2d California Cavalry. It matches earlier plan (below) with few exceptions. Officers' quarters has been added at open eastern end of parade ground; sutler has moved to building at far left of sketch; several small buildings have been added as store houses or shops.

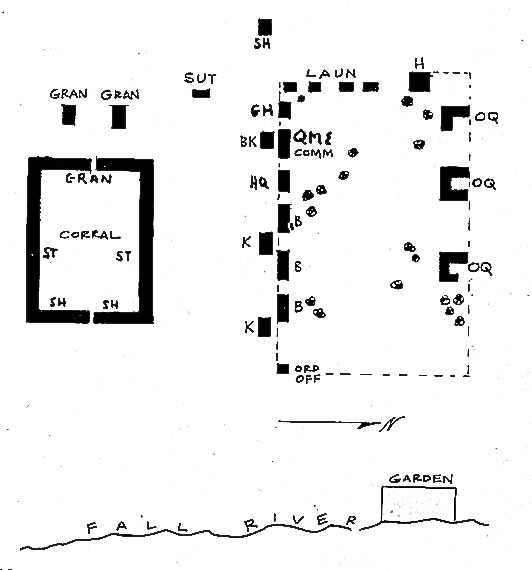

| B | Barracks |

| BK | Bakery |

| GH | Guard House |

| GRAN | Grainery |

| H | Hospital |

| HQ | Headquarters |

| K | Kitchen |

| LAUN | Laundress Quarters |

| OQ | Officers' Quarters |

| QM & COMM | Quartermaster and Commissary |

| ORD OFF | Ordnance Office |

| SH | Storehouse |

| ST | Stables |

| SUT | Sutler |

Fort Crook was drawn in 1859 by Inspector General Mansfield "A little more improvement in the buildings and stables will make them quite suitable and comfortable," he reported. "These buildings are all of logs and shingled with adobe chimneys and hearths." Mansfield added that guardhouse was empty except for Indian prisoners, barracks did not have bunks, and troops were poorly drilled. (Redrawn from Mansfield Report 1858.)

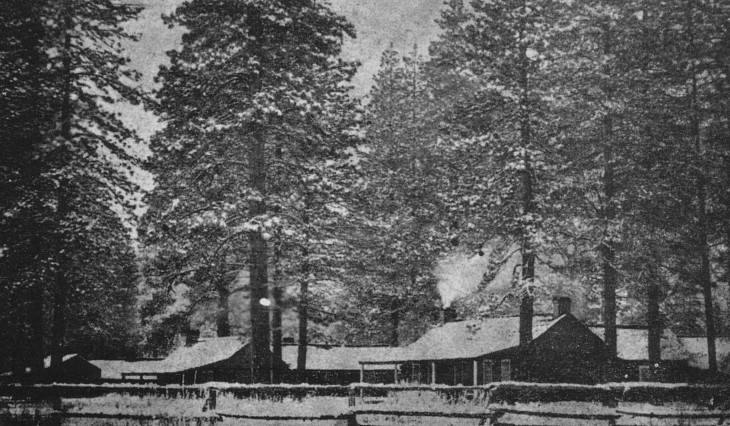

The officers' quarters at Fort Crook were photographed in late 1850's by Lieutenant Lorenzo Lorain. At start of Civil War, half of garrison was sent to protect San Francisco Presidio. Reinforcements come after reports included typical patrols such as in 1861 when 30-man detachment covered 302 miles in eight days. The commander frequently complained that settlers sent 100 miles for his aid, even though they had more men and better arms and could have started immediate pursuit.

George Crook was there but he was not founder of Fort Crook. His diary says: "About this time Capt. J.W.T. Gardiner, 1st Dragoons, arrived on Fall River to establish a post, which he did, and named it after the undersigned." plaque (left) apparently as modelled after old fort building (right), shown as it was 1900.

This page was reprinted with permission from Pioneer Forts of the Far West, published in 1965