Northern California's 184th Infantry Regiment (2nd California) during World War II

Between the end of the First World War and the beginning of the Second, the National Guard was far less of a fighting force as it is today. Some joined their local regiments to get away from the wife and kids once a week and a couple of weeks in the summer of light adventure. There were also those who also knew that the Great War for Civilization would not be "... the war to end all war."

For the most part, the normal peacetime routine of weekly drills and annual camps lasted throughout the 1920's and 1930s. An exception was November 24, 1927. That month, prisoners at the Folsom State Prison seized control of the main buildings and took several of the staff as hostages. The warden was unable to control the situation and asked the Governor for the National Guard. Telephone calls and announcements over the radio were made. Theaters stopped their shows to announce "...all National Guardsmen report to your armory." The entire 184th Infantry Regiment, and supporting troops, under the command of Colonel Wallace Mason, assembled and moved to Folsom. When the action was over, 11 were dead and 11 wounded. For more information concerning the Folsom Prison Riot, CLICK HERE

For the rest of the 1930s the unit kept

busy with their weekly evening drills and the "summer camp"

at Camp Merriam between San Luis Obispo and Morro Bay. Several

of the enlisted members who had joined the unit during the twenties

and thirties would work their way through the noncommissioned

and commissioned officer ranks. One of the most notable was Sacramento

dentist Roy A. Green, who joined the 184th as a private in 1918,

and went on to be commissioned and command Company A, the 1st

Battalion, and later the entire regiment. He was eventually to

become a Major General, commanding the 49th Infantry Division.

There were others, at least one other general officer, and several

colonels.

Mobilization and War

But the peacetime routine was not to last long. When France fell in the summer of 1940, President Roosevelt decided to bolster the Regular Army. There was the introduction of a peacetime draft, and in 1941, there was a general mobilization of the National Guard. The 184th, as well as the rest of the 40th Infantry Division mobilized on 3 March 1941. They moved from their armories in Sacramento to their old training grounds at what was now known as Camp San Luis Obispo. Most of the regiment thought that they would be on active duty for only a year. However, on 7 December 1941, that all changed.

Within 48 hours of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the regiment moved to the San Diego area and took up defensive positions for the expected attack or invasion of the West Coast. While the rest of the regiment garrisoned area such as Del Mar, La Mesa, and Lindbergh Field, Company A was sent to San Clemente Island. If the Japanese attack had occurred, this lone company of Sacramentans would have been decimated since there was no avenue of retreat or reinforcement.

They were to remain there until April when they moved to Fort Lewis, Washington and later the Presidio of San Francisco.

While at the Presidio, the regiment was relieved from the 40th Infantry Division and attached directly to the Western Defense Command. In November 1942, the regiment was attached to the 7th Infantry Division at Fort Ord and later Amphibious Training Force Nine. It was during this period that the regiment was reinforced and its title modified to "184th Regimental Combat Team" In July 1943 the regiment left San Francisco bound for the Japanese held Aleutian Islands. The 184th arrived on Adak Island for training and was assigned again to the 7th Infantry Division.

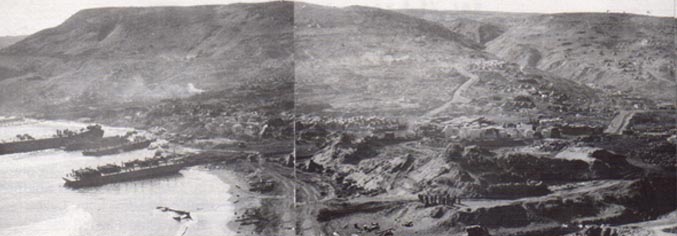

Operation COTTAGE: The Landings on Kiska

On 15 August 1943, Operation COTTAGE, the retaking of the last

Japanese held island in the Aleutians commenced. The 184th, augmented

by the 1st Battalion, 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment, and with

the 13th Canadian Infantry Brigade Group on its right, made its

first of many assault landings at Long Beach on Kiska Island.

When the regiment landed, its commander, Colonel Curtis D. O'Sullivan,

ordered the regiment's band to play. They responded with "California,

Here I Come," and "The Maple Leaf Forever." After

an unopposed landing, the regiment found that the Japanese garrison

had been evacuated by a large cruiser and destroyer force on 28

July. The enemy had left in such a hurry, that they left mess

tables still set with meals, and blankets soaked in fuel oil,

but not lit. Nevertheless, the 184th did have the honor of being

the only National Guard regiment to regain lost American territory

from a foreign enemy in World War II, the first since the War

of 1812.

When the island was declared secure, the division moved to Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, arriving in September of 1943. This was a welcome change for the men who just spent over three months on the Alaskan islands. However, it did not last long. On 20 January 1944, the regiment left Hawaii bound for the Marshall Islands.

Kwajalein

Kwajalein Atoll had been Japanese territory

for decades. As such, they had many opportunities to build a complex

system of fortifications. On 1 February, the 184th along with

the 32nd Infantry Regiment assaulted the heavily defended atoll.

Two days later, A, B, and C Companies were given the assignment

to clear the highly fortified blockhouse sector. When the battle

for Kwajalein was over, approximately five days later, over 8,000

Japanese, members of the 61st Naval Guard Force were dead. General

George C. Marshall, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, later

said that the operations on Kwajalein were the most efficient

of the war. Once again, the 184th achieved another first. They

were the first National Guard unit to seize and hold territory

that Japan held prior to the start of the war.

With the island secure, the 184th re-embarked on to their transports and returned to Hawaii for rehabilitation and more training. On 15 September 1944, they departed Hawaii, bound for Eniwetok Island. Initially, this was to be a staging area for the invasion of Yap Island, but when they arrived, they found that the operation was canceled in favor of a larger landing, the liberation of the Philippines.

Leyte

On the morning of 20 October, the 184th hit the beaches near Dulag on the east coast of the island of Leyte. With the beachhead secured, they moved inland. The island provided the Japanese with an ideal defensive terrain. Leyte is a large island, covered with mountains, rain forests, and swamps. The Japanese were long accustomed to fighting in the jungle, and had over three years of occupation to learn the terrain and plan defenses. Additionally, it was easy for the Japanese to reinforce their garrison on Leyte from Luzon in the north and Mindanao in the south.

The Japanese 34th Army, consisting of four divisions, including the infamous 16th Division that was credited for the "Rape of Nanking" and the "Bataan Death March", was the primary opponent on Leyte. The 184th pushed on through the Dulag Valley experiencing high casualties. When the Japanese counterattacked the 32nd Infantry Regiment, which had spread out along the Palanas River, the 184th was sent to reinforce them. Several attacks were repulsed and the enemy was driven into the bamboo thickets. This action later became known as The Battle of Shoestring Ridge. The 11th Airborne Division relieved the division, less the 17th Infantry Regiment, on 28 November 1944. The division then moved to Baybay, and the 184th started a drive from Damulaan towards the port of Ormac. They then seized the town Albuere and had joined up with soldiers of the 77th Infantry Division, which had landed near Ormac.

The remainder of the 7th then moved to Ormac to regroup. From there, they spent several weeks landing on and securing several of the small islands that surround Leyte. On 10 February, they were relieved by the Americal Division and started to prepare for the Ryukyus Campaign. When the division left, they were credited with inflicting over 54,000 enemy deaths.

Okinawa

On 1 April 1945, the division landed on Okinawa. By now, Colonel Roy A. Green was commanding the regiment. Initially the 7th and 96th Infantry Divisions were to clear the southern end of the island. Fortunately for these thinly spread forces, an expected counterattack did not occur. If it had, there was a possibility that they could have driven the invasion force into the sea. A few days after the landing, the 184th came into contact with elements of the Japanese 32nd Army on the heavily fortified Kakazu Ridge. On 9 April, with the assistance of massed artillery fire, Tomb Hill was captured. By now, companies were losing 30 to 50 men per day. Rifle companies of 40 or 50 men became the rule. On 1 May, despite the presence of infiltrators, the 184th attacked and briefly held Gala Ridge before losing it to a counterattack. Both sides traded blow for blow until the Japanese fell back to their final defensive positions along the Naha-Shuri-Yanabarau Road. In keeping with their motto, "Let's Go", the 184th , using a rainstorm to cover their movements, outflanked the Japanese positions and effectively cut off their forces on the Chenin Peninsula. All that was left to do was mop up the scattered pockets of resistance on the peninsula. When Ryukyus Campaign ended, the Japanese 32nd Army had lost tens of thousand of its soldiers. The 184th had lost hundreds.

Next, the division began planning for an invasion that was to make Okinawa look easy, the invasion of the Japanese Home Islands. Fortunately, the dropping of the Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended the need for the landings. If they had taken place, some predicted that over a million deaths would have occurred on both sides.

Instead, the 7th was rushed to Korea to disarm the Japanese garrison there and to provide an occupation force. When the regiment arrived in Seoul, the honor of accepting the surrender of all Japanese forces in that region fell upon Colonel Green and the members of Sacramento's 184th Infantry Regiment. While there, the regiment would lose many of its members to rotation. There were few of the original members of 184th left now. All had earned their Combat Infantry Badges or Combat Medical Badge. Most of them had earned the Purple Heart and the Bronze Star Medal for valor. Some even earned the Silver Star. Those who didn't have enough points to be rotated home were used to help reform the 31st Infantry Regiment that had been destroyed on Bataan. It is ironic that the 184th, who helped destroy the Japanese 16th Division, would be rebuilding the regiment destroyed by the 16th.

When the 31st Infantry Regiment was fully reconstituted, it replaced the 184th in the 7th Infantry Division's Order of Battle, and on 20 January 1946, the colors were cased and the regiment inactivated. The 184th would maintain links with the 7th, 31st, and 32nd Infantry Regiments for many years after the war. The 184th Infantry Regiment had participated in some of the toughest fighting of the war, and it is evidenced by the streamers embroidered ALEUTIAN ISLANDS, EASTERN MANDATES (with arrowhead), LEYTE (also with an arrowhead), and RYUKYUS. Also, the President of the Philippine Commonwealth presented the regiment The Philippine Presidential Unit Citation for their part in liberating the people of the Philippines.

The regiment was reformed almost a year later in Sacramento as a part of the newly formed 49th Infantry Division, and it quickly settled down into the cycle of drills and annual training at Camp San Luis Obispo. Today, the 1st Battalion (Air Assault), 184th Infantry Regiment (2nd California), headquartered in Modesto, continues that tradition of service to the state and the nation.