The United States Army learned many hard lessons during the Civil War, and one of the hardest was that all the nation's permanent fortifications had become obsolete. Multi-tiered masonry forts (such as Fort Point) had proven themselves in battle to be little more than oversized targets for artillerymen. At the end of the War, the Army realized it needed to radically redesign all its forts. Today, hidden away at Fort Baker, is a pristine example of the military designers' solution to that post-Civil War dilemma: the earthwork fortification of Battery Cavallo.

Prior to the Civil War, the Army's Corps of Engineers constructed dozens of brick and masonry fortifications around the nation's harbors and rivers. More than thirty of these defensive "works" (as the military called them) dotted the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, and two had even been erected in far-off California at Fort Point and Alcatraz Island. But in their efforts to place larger numbers of cannon in single structures, the Engineers had begun constructing forts several stories high. As the forts became taller they also became easier targets for gunners.

During the late 1860s, the Army experimented with various ways to "bomb proof" existing forts. Proposals ranged from hanging metal plates on their exterior faces to replacing them entirely with rotating iron gun turrets. More conservative Engineers, however, studied Civil War battlefields where dirt earthworks had been extensively used. These improvised fortifications, they noted, had been simple to build, provided excellent protection against enemy fire, and were easy to maintain and repair. Earthworks, they decided, would become be the basis of the next generation of permanent American forts.

The Army's standardized designs, known as "The Plan of 1870," called for cannon to be mounted in low-profile earthwork batteries with each pair of guns separated from the next by artificial hills called "traverses." Within the traverses would be masonry magazines, store rooms and tunnels for moving troops and supplies

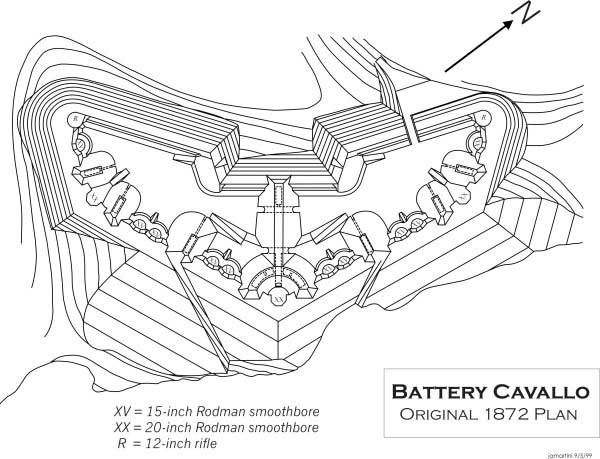

This 1872 plan clearly shows Cavallo's arrowhead shape. Gun positions are indicated by semi-circular platforms, and underground rooms and tunnels by dotted lines. Guns on the right flank faced the Presidio, while those on the left faced Angel Island and Alcatraz. (John A. Martini)

San Francisco was to be liberally protected with earthwork batteries, the largest and most elaborate of which was "Point Cavallo Battery" in Marin County. There, on a flat bluff overlooking Horseshoe Cove, the Army designed a work unlike anything else on the Bay.

Battery Cavallo was to be unique in several respects. Instead of arranging its cannon in a simple line, the Engineers designed Cavallo in the shape of a broad arrowhead pointing into San Francisco Bay. They also provided the battery with a high earthen parapet on its landward side, in effect creating a totally enclosed earthen fort. In order to protect the battery from raiding parties, the designers provided it with a single easily defended gate and "firing steps" for riflemen to use in case of assault from the rear.

Cavallo was also to have had the most massive firepower of any battery on the Pacific Coast. Its anticipated armament of thirteen guns included Parrott rifles, 15-inch smoothbore Rodman cannon, and three monstrous 20-inch Rodmans. These latter weapons, weighing nearly 100,000 pounds apiece, would be able to fire 1,000 pound cannonballs over four miles.

By late 1874 the structure was nearly complete, awaiting only a few finishing touches and the arrival of its artillery. The new work had cost $107,825 up to that point.

However, military cutbacks and evolving technology made the Cavallo obsolescent before it was even armed. Construction on all fortifications around the nation halted in 1876. (Of the much-vaunted 20-inch Rodman guns only two were ever cast, neither of which left the East Coast.) It wasn't until the Spanish-American War that the first guns were mounted in Cavallo when three 8-inch rifles were emplaced in 1898. These guns were short-lived, and records show they were removed by 1910.

Over the years, most earthworks around the country have disappeared beneath subsequent construction, but Battery Cavallo's earthworks have survived intact. Used occasionally for storage and as an antiaircraft emplacement during World War II, the battery was nearly forgotten in recent decades. During the Cold War its manicured traverses and parade grounds began giving way to encroaching vegetation.

The biggest threat to Cavallo came from increased visitation to Fort Baker during the 1970s and '80s, especially from users who saw its mounded earthworks as excellent off-road biking terrain. In more recent years, the Army and the National Park Service have worked together to restrict access to Battery Cavallo. This was done both to preserve the historic earthworks and also to protect an area in front of the battery that provides habitat for the endangered Mission Blue butterfly.

Battery Cavallo today is a challenging example of the National Park Service's dual mission of protecting historic and natural resources for the enjoyment of future generations. Can a historic structure that is also home to an endangered species be managed to protect both resources? And can visitors be allowed to explore these fragile resources?

The park believes it can meet these challenges at Battery Cavallo, and we are currently developing a management plan that will ensure greater protection to the area while simultaneously allowing controlled visitation. Interpretation will be a key element of this plan, because through interpretation of Cavallo will come understanding of its varied resources, and through understanding will come appreciation and protection of resources throughout the park.