History

It is necessary to clearly understand the situation in California as it was on July 7, 1846, the day Commodore John D. Sloat hoisted the "Stars and Stripes" over Monterey. To begin with, the Gavilán Peak episode between General D. José Castro and John C. Frémont's expedition, in March 1846, caused United States Consul Thomas O. Larkin, Jr., to appeal for protection from the Pacific Squadron of the U.S. Navy (1). In response the sloop USS PORTSMOUTH reached Monterey on April 22, 1846. While this was only a precautionary measure, as history bears witness, it set in motion a series of events that led to the conquest of Los Angeles and thereby California.

The Republic of California, commonly referred to as the "Bear Flag Republic," ceased to exist by the unanimous consent of the Americans who composed it, the moment the "Stars and Stripes" replaced the last Bear Flag flying at Sutter's Fort on July 11, 1846. Thus the short-lived Bear Flag Republic ceased to exist twenty-eight days after it had began. The Bear Flag Republic devolved upon its participants to perform the task of wresting the Province from Mexico (2).

Commodore Sloat was cognizant of Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones' premature capture of Monterey in 1842 (3). To make matters worse, to the best of Sloat's knowledge, the United States was not at war with Mexico. So it was with great reservation that Sloat raised the American flag in accordance with standing instructions he had received from Washington should war be declared.

To recap, the Pacific Squadron had been patrolling between the Sandwich Islands and Mazatlan, on Mexico's west coast, for many months, awaiting a message from the Navy Department on war. Sloat, however, possessed no evidence that war had been declared. Furthermore, he had no instructions to set up any form of government in California on behalf of the United States (4).

In order to calm the fears of the Californios –and by the term "Californios" is meant the Mexican inhabitants –and also to make his position clear, Sloat issued a proclamation prior to raising the flag at Monterey. This proclamation is important for it serves to make clear in the minds of the present-day reader the exact situation at that time, and Sloat's position and point of view.

It should also be pointed out that during the Mexican War, Los Angeles was considered the most important city on the Mexican-held Pacific Coast. Even though the flag of the United States had been raised over the customs-house at Monterey by sailors from Sloat's flagship, the USS SAVANNAH, without firing a shot on July 7, 1846, a feat duplicated at both Yerba Buena (San Francisco) and Sonoma by forces under command of Captain John B. Montgomery of the USS PORTSMOUTH on July 9, and at Sutter's Fort only a few days later, the simple fact of the matter was that Pueblo de los Angeles was at that time the capital of the Province of Alta California.

The Territorial Legislature of the Mexican Congress, in 1835, established the capital of Alta California at the Pueblo de los Angeles. When Pio Pico entered upon the duties of governor, he did so with a desire to bring peace and harmony to Alta California. Only the military headquarters, the archives and treasury remained at Monterey, with the principal offices of the territory divided equally between northern and southern California.

So even though the flag of the United States was raised over Monterey and Yerba Buena, the occupation of Pueblo de los Angeles was not effected until its was taken possession of by the combined forces of Commodore Robert F. Stockton and Colonel John C. Frémont on August 13, 1846.

Stockton, having succeeded Sloat, learned of Gen. Castro's stand at Los Angeles. On taking command of the Pacific Squadron on July 29, he immediately made preparations to capture the city. Sloat did not approve of Col. Frémont's actions setting about the Bear Flag Revolt or Stockton's policies to conquer California.

Frémont, who had come to Monterey from Sutter's fort with his battalion of 120 men, was ordered by Stockton to proceed to San Diego. He was ordered to take that place, and then to march north, meet Stockton near Los Angeles, and take the capitol at the Pueblo de los Angeles. On July 26, Frémont and his men set sail on the CYANE. A week later, on August 1, Stockton departed in the frigate CONGRESS with 350 marines and sailors for San Pedro.

With this in mind, let us now turn our attention to Los Angeles and learn how affairs progressed at the capital.

Commodore Stockton had brought Mr. Thomas O. Larkin, the American Consul, with him to San Pedro. Larkin had high hopes that he might negotiate the peaceful annexation of California. Before departing Yerba Buena, Larkin had written to both Governor Pio Pico and Gen. Flores advising them to endeavor to make terms with Stockton.

On August 6, 1846, Stockton put ashore the ship's Marines, under First Lieutenant Jacob Zeilin, and seized San Pedro without firing a shot. They immediately proceeded to established the Navy's first base in San Pedro. This would be the first military base established by the United States, much less a naval base, any where near Los Angeles. Upon landing, the men began a week of drilling in land tactics in preparation of the twenty-five mile march to Los Angeles.

At that time, both Castro and Pico were then together in Los Angeles and they sent a delegation to San Pedro to negotiate with Stockton as soon as news of his arrival had reached them. In this delegation were Pablo de la Guerra and Jose Maria Flores, the later very soon afterwards became Comandante General of the California military forces.

Commissioners Guerra and Flores delivered a letter to Stockton in which Castro expressed a general willingness to negotiate for peace provided the "all hostile movements be suspended by both forces." This gentlemanly proffer seemed reasonable to Larkin, but Stockton absolutely declined to treat with Guerra and Flores as the ambassadors of Castro and Pico or in any other capacity. Stockton rejected all terms of peace but sent Larkin ahead under a flag of truce with his reply.

Stockton's message, dated August 7, stated, "I do not wish to war against California or her people; but as she is a department of Mexico, I must war against her until she ceases to be a part of the Mexican territory. This is my plain duty." He insisted upon Castro's unconditional surrender and ended the letter with ". . . if, therefore, you will agree to hoist the American flag in California, I will stop my forces and negotiate the treaty."

Castro rejected the proposal, considering it humiliating, and conferred with Governor Pico, after which the assembly met and was dissolved.

Five days later, on August 11, a mixed body of sailors and Marines began a march from San Pedro to capture Los Angeles. Stockton again sent Larkin, with two other officers, ahead to Los Angeles with a letter to Castro. Larkin met with no resistance on the road to Los Angeles and enter the pueblo only to find the Government House abandoned.

It has been suggested by many writers on the subject that Gen. Castro tried a bluff. One such story suggests that Castro sent word to Stockton that "if he marched upon the town he would find it the graves of his men." Accordingly, came the Commodore's laconic reply, "Tell the General to have the bells ready to toll, as I shall be there tomorrow." There is little real historical support for this exchange of communication, as Castro's forces, along with Governor Pico, had already made a hasty retreat from Los Angeles.

Larkin, having found that Castro and Pico had fled, so notified Stockton. Stockton sent a portion of his marines back to the ship and continued his march with the balance. By the time Stockton had reached the outskirts of the town, Frémont and his battalion had joined forces.

On August 13, with band playing and colors flying, the combined forces of Stockton and Frémont entered Los Angeles, without a man killed nor gun fired. The pueblo of Los Angeles offered no resistance, and the Americans established military headquarters on Main street. Stockton simply declared martial law, organized a military company, and put Benjamin (Don Benito) Wilson in command, who joined forces with Frémont and his men, leaving only a small contingent of fifty marines to occupy the pueblo under Capt. Archibald H. Gillespie, U.S.M.C.

Stockton, as commander of the Pacific Squadron, issued a proclamation to the people, signing himself "Commander-in-Chief and Governor of California" on August 17, 1846. The proclamation announced that the country was now the possession of the United States and California would be governed like any other territory of that nation, but meanwhile by military law.

Evidence shows that the President James K. Polk had signed the Declaration of War against Mexico on May 13, 1846, but the Pacific Squadron of the U.S. Navy in the California Theater had no direct knowledge that war existed until the sloop WARREN sailed into Monterey on August 12.

It should be remembered that everything up to this point had been done based on Frémont's earlier acts. Interestingly enough, it was on August 17, that the war-ship WARREN anchored at San Pedro bringing definite news of a declaration of war to Stockton and Frémont.

On September 2, 1846, Stockton divided California into three military districts. A few days earlier, he named Frémont military commandant of the new territory and installed Lieut. Gillespie as alcalde of Los Angeles. Among his last duties before departing Pueblo de los Angeles, Stockton ordered Kit Carson to Washington with a full report to President Polk and Secretary Bancroft. Stockton, in a letter dated August 26, 1846, reported to the Secretary of the Navy:

"Thus in less than a month after I assumed the command of the United States Forces in California, we have chased the Mexican Army more than three hundred miles along the coast; pursued them thirty miles in the interior of their own country, routed and dispersed them; and secured the territory to the United States; ended the war, restored peace and harmony among the people; and put a civil government into successful operation."

Larkin heartily approved of Stockton's conduct and so reported to Buchanan that "[p]erhaps no officer in our Navy is better adapted for the capture, charge and care of Califoria." He applauded Stockton's appointment of Frémont as military commandant of California and the commodore's plan for a provincial civil government, outline in a draft of a constitution which Larkin termed "The Organic Law of his Empire."

With Los Angeles now under control of American forces, on September 5, Stockton ordered the naval force to withdraw back to San Pedro, proceeding from that place for Yerba Buena (5). Frémont and his force was ordered to take the overland trail northward, the agreement being that the two commanders with their forces were to meet at Yerba Buena---on October 26.

Southern California now seemingly pacified, the scene shifted northward, back to Monterey and Yerba Buena.

With California in his possession and armed with the fact that war had been formally declared by the United States against Mexico, Stockton set about organizing a government for the conquered territory. The conquerors of California, Stockton and Frémont, now turned their attention to making plans for the occupation of Mexico. The plan called for Frémont to assume control of California and Stockton, with a full regiment of sailors and marines, to undertake a naval expedition down Baja California, sail around Cabo San Lucas, take on supplies at Mazatlan, and proceed south by southeast to Acapulco. There he would disembark and march overland 250 miles north to Mexico City to "shake hands with General Zachary Taylor at the gates of Mexico."

Back in Los Angeles, things might have remained peaceful, except that Capt. Gillespie was left in charge of Los Angeles. The placing of the pueblo under martial law greatly angered the Californios. Leaving the city in command of a U.S. Marine only angered the Angeleños more. At the end of September, about 300 Angeleños staged a revolt, under Gen. M. Flores, taking a solemn oath not to lay down their arms until they had driven out "the accursed Americans."

The American garrison left in charge of Los Angeles was quite small, and on September 23, 1846, the local inhabitants revolted against the occupying force. About twenty men led by Cérbulo Varela exchanged shots with the Americans in their quarters at the Government House. The attack struck a spark to the latent hostility against the garrison and by nightfall Los Angeles was in arms against the occupying force.

Meanwhile, the first battle of the war took place at the Chino Rancho about twenty-five miles east of Los Angeles in the neighborhood of which Stockton had directed some twenty Americans to keep in close touch with one another for the purpose of guarding the San Bernardino frontier against the possible return of Castro and an armed force from Mexico.

On September 26-27, 1846, Flores sent Serbulo Varela with about fifty men to route the Americans at Chino. Jose del Carmen and others, marching from the opposite direction, joined forces with Varela. The Americans were attacked in the adobe ranch house where they had assembled. Neither side was supplied with much ammunition. The Californios on their horses assaulted the house, firing their guns from the backs of the animals. The Americans returned the fire, but the Californios succeeded in getting close under the walls of the house and setting the roof on fire. The Americans then came out and surrendered and were taken prisoners to the camp of the Comandante Flores, just outside of Los Angeles.

The result of the battle was one Californio killed and several wounded and three Americans wounded seriously.

Back in Los Angeles, Gillespie, having found himself in a serious situation, withdrew from their headquarters in town and posted his men on Fort Hill. Unfortunately, Gillespie had not first determined whether the position had water, which it did not. Gillespie was caught in a trap, surrounded, with only a few men, with no water and no supplies. Within a few days nearly 600 well-armed Mexicans would surround the hilltop garrison of Gillespie and demand its surrender. They were outnumbered ten to one by the enemy. John Brown, an American, called by the Californios Juan Flaco, meaning "Lean John," succeeded in breaking through the Mexican lines and riding with all speed to Yerba Buena he delivered to Stockton a dispatch from Gillespie notifying him of the situation.

Flores called on Gillespie to surrender, pointing out to the Americans that their situation was hopeless and that any resistance offered on their part could result only in an unnecessary sacrifice of human life. The Californian Commander offered to permit Lieutenant Gillespie and his men to withdraw with their colors and arms and all the honors of war. Flores also offered an exchange of prisoners (6).

Gillespie, on September 30, finally accepted the terms of capitulation (7) and departed for San Pedro with his forces, accompanied by the exchanged American prisoners and several American residents. The Americans arrived in San Pedro without molestation and four or five days later embarked on the American ship VANDALIA, on board of which they remained in the harbor awaiting instructions from the north.

Gillespie took two cannon with him when he evacuated the city and left two spiked on Fort Hill. There seems to have been a proviso in the articles of capitulation requiring him to deliver the guns to Flores on reaching the embarcadero. Instead, he spiked the guns, broke off the breech knobs and trunnions and rolled one of them into the bay.

Flaco Brown, the courier that had been sent out by Gillespie from Los Angeles, found Stockton at San Francisco on October 1. The news alarmed Stockton since he had but a short time before officially declared the conquest of California complete and all that remained for him to do was to establish a civil government. He resolved upon immediate action. Frémont had been ordered to proceed by water to Santa Barbara, so Stockton prepared to sail with a force to San Pedro for the relief of Gillespie and the recapture of Los Angeles.

On the way down the coast the ship STERLING, in which Frémont with one hundred sixty men had set sail, met the VANDALIA from San Pedro, and Frémont then learned of the situation at Los Angeles. Taking matters in his own hands, as he frequently had done before, he determined to return to Monterey. The ship met with bad weather. There Frémont's forces were joined by other Americans and, proceeding to San Juan Bautista, he began his march southward on November 26, with an army consisting of about five hundred men, fairly well mounted and equipped with muskets in addition to four brass field pieces.

In the meantime, as Stockton was sailing for San Pedro, he was informed that Monterey, which he believed to be unprotected, was threatened with attack, so he hastened to that point, sending Captain William Mervine on to San Pedro.

Fog delayed the SAVANNAH's departure until October 4. She reached San Pedro two days later to find the VANDALIA at anchor with Gillespie's men still embarked. After conferring with Gillespie, Mervine decided to march immediately to Los Angeles.

On October 7, Mervine's forces, joined by those of Gillespie, numbering about three hundred fifty men, landed and proceeded to mount an attack against Los Angeles.

Mervine's troops camped at Rancho San Pedro, taking over everything but the Dominguez family house. That night a group of about 200 Angeleños took positions at the Los Angeles River below Dominguez Hill. During the night the Californians started sniping at the American bivouac. At daylight, Mervine's troops attempted proceeded on the road they were met by a party of Californians. The Americans were unable to move North. The battle of Dominguez Ranch ensued.

The Angeleños had hitched a cannon to some horses which they would fire and then retreat, and then fire again. The result to the Americans was disastrous with the loss of four men killed and several wounded (8). Believing that he was faced by a superior force, Capt. Mervine was compelled to retreat back to San Pedro. American troops made several tries to re-occupy Los Angeles, but had little success.

After landing reinforcements at Monterey, the CONGRESS resumed her voyage to San Pedro but missed Frémont. Stockton's flag ship, the CONGRESS, arrived at San Pedro on October 23. The SAVANNAH was still lying at anchor in the harbor. The following morning the two frigates landed their Marines, a detachment of sailors, and Gillespie's men. Although the Californians neither contested the landing nor harassed the American encampment, after reassessed the situation, and based on the intelligence that the Angeleños possessed a superior force, Stockton concluded to continue on his course and retake Los Angeles from the south.

Stockton sailed with the whole expedition to San Diego, having doubtless been convinced that the Californians were not to be so easily whipped as he had supposed. His plan was to secure a safer anchorage for the ships in the harbor of San Diego and after a thorough reorganization at that port, march his forces up through the interior and prosecute the war by land. It was there, in San Diego, that Stockton would combine his forces with Brigadier General Stephen W. Kearny and Colonel Philip St. George Cooke and the Morman Battalion.

Meanwhile, after the expulsion of Gillespie and his men from Los Angeles, detachments from Flores' army were sent to Santa Barbara and San Diego to recapture these places. Stockton's shift of base to San Diego handed Flores badly needed time to organize his forces. And, with this in mind, it would take the American forces nearly three months before the Americans would retake Los Angeles.

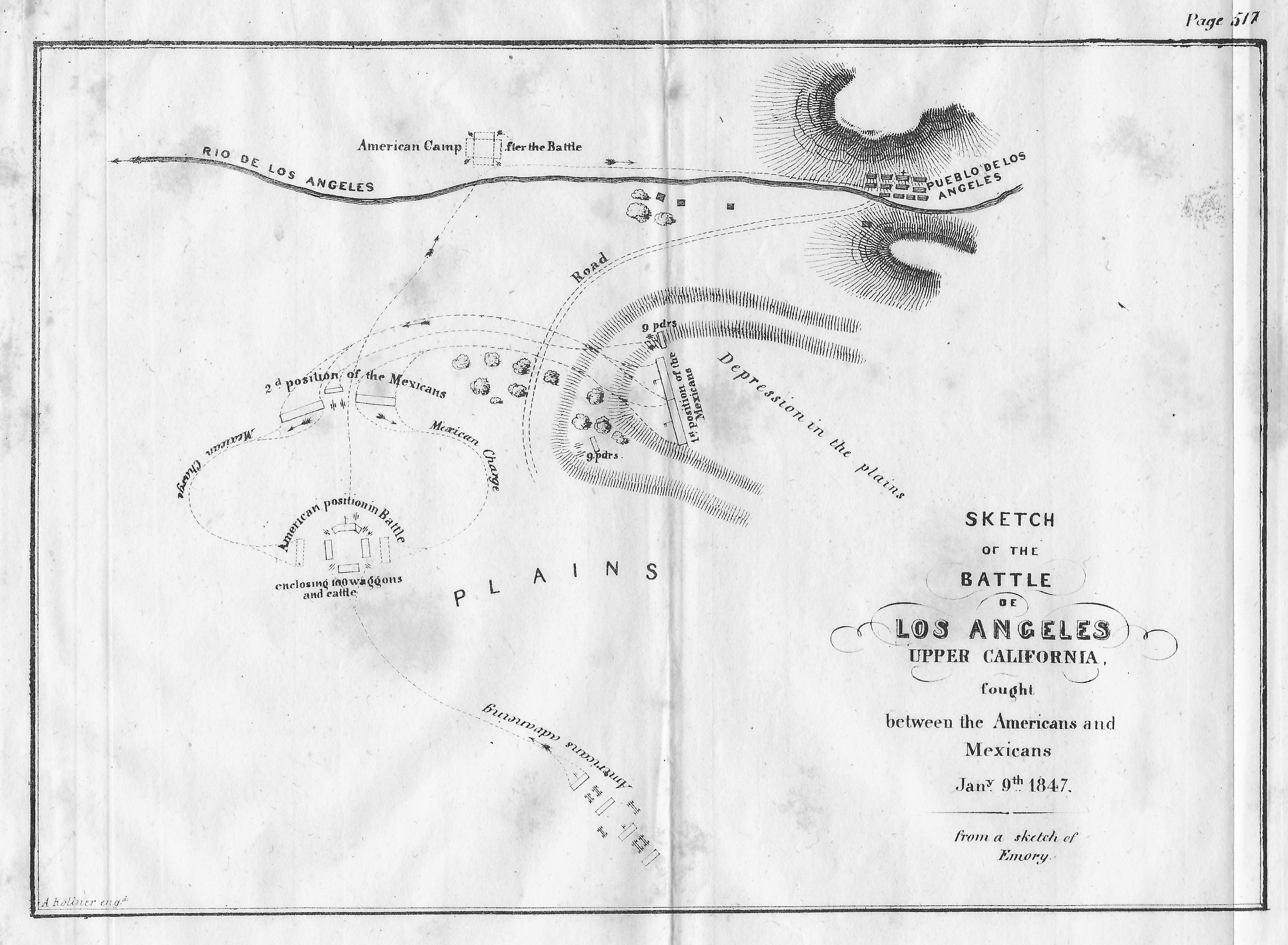

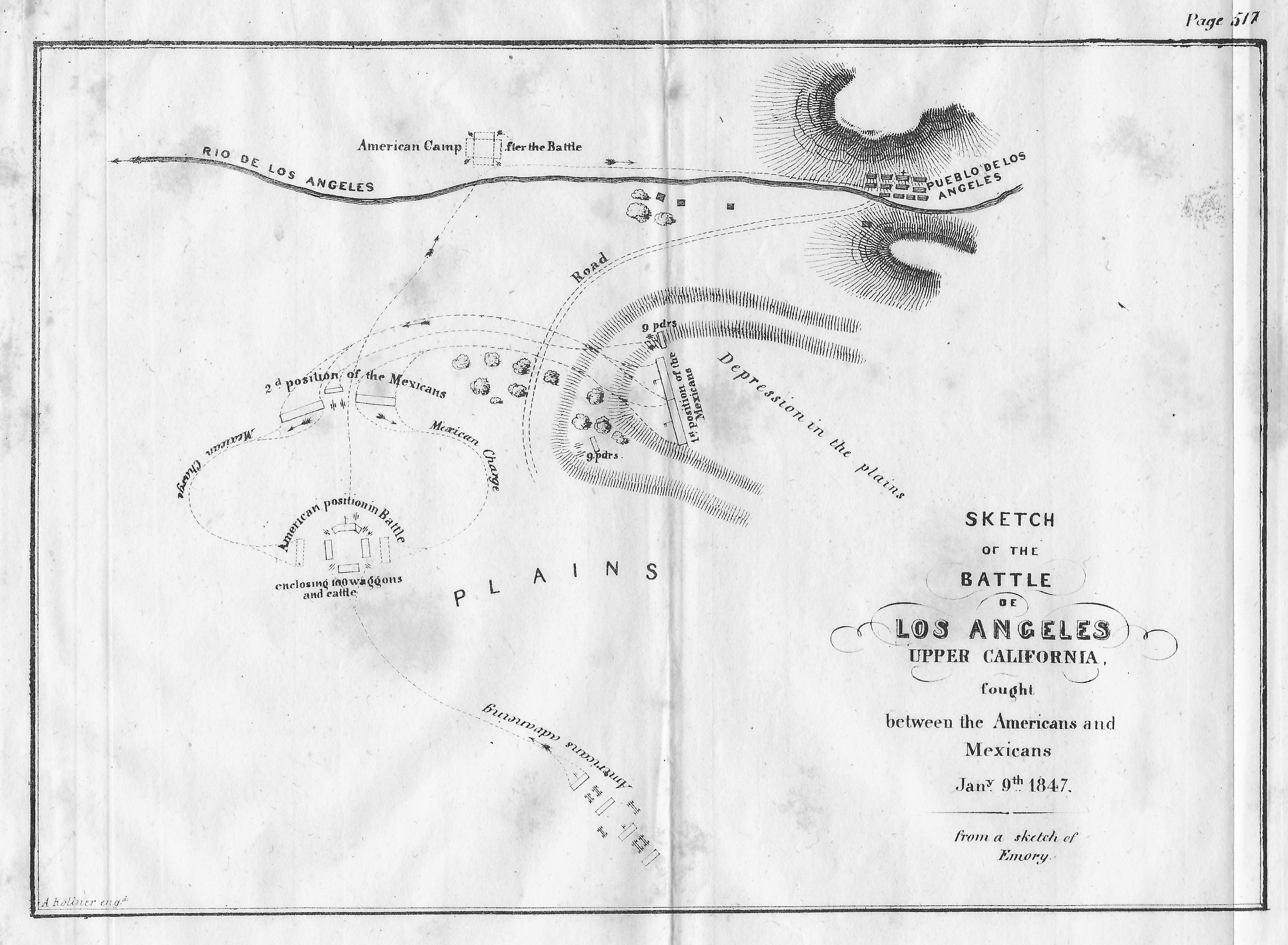

In January of 1847, the last two serious military engagements against U.S. forces invading California were fought below Los Angeles.

With the dragoons' arrival all of the forces available for the decisive Los Angeles campaign were in position. Stockton set his force in motion on December 28 and 29. When the last units departed San Diego, the force numbered 607 men. To the north, Frémont was making his way south.

On January 7, Stockton's troops camped near the ranch house on Rancho Los Coyotes. Their resting spot was near a stream that is a tributary of Coyote Creek. The officers were entertained at the ranch house on Rancho Los Coyotes while the troops prepared to march on to Los Angeles the next day (9).

In the meantime, the Californios were planning an ambush at the San Gabriel River. Flores prepared to ambush Stockton's men at La Jaboneria Ford on the river. Fortunately, during the night, Stockton's scouts discovered the Californians and he ordered his men to cross at a higher point –Bartolo Ford. Flores followed suit and was able to take up position before the slower-moving Americans reached the crossing. The American forces received word of the ambush and were prepared when they met Flores' forces at the river.

On the morning of January 8, about 350 Californios led by Flores and Pico offered the last serious Mexican resistance against U.S. forces at the Battle of the San Gabriel River. There Mexican defenders attempted to block the march of U.S. Army and Naval troops, commanded by Kearny and Stockton, advancing from the direction of San Diego.

At the Battle of San Gabriel, however, the Californians were not successful in facing Stockton's offensive. The Americans possessed superior firepower and a more professional military force. After two hours of artillery duels, infantry and cavalry charges, the Californians saw no chance of victory and conceded the Battle of the San Gabriel River by withdrawing (10).

The Mexican forces retreated, falling back to the Los Angeles area. What remained of the beaten Mexican force retreated to an encampment in La Mesa –what is now Pasadena. Here, another military skirmish occurred on January 9, 1847. After nearly an hour of artillery duels, infantry and cavalry charges, Flores found himself unable to match the American forces superior firepower. The Californios were again forced to withdraw.

After hearing of the final military outcome, on January 10, 1847, the leaders from Los Angeles came out to surrender the city peacefully to the American military force.

Flores, seeing the situation as hopeless, now moved north of the city. In the meantime, Frémont arrived in the Los Angeles area from the north and occupied Mission San Fernando.

While encamped at the San Fernando Mission, Frémont dispatched Jesus Pico, a man of some influence in the Mexican community, to persuade the remaining Mexican forces to surrender. With Flores still present, it was decided to follow the advice of Jesus Pico. On January 12, as Flores turned over command to his deputy, Andres Pico, and headed south to Mexico. That day, representatives from the Mexican camp returned with Jesus Pico to meet with Frémont to determine the terms for a capitulation.

On January 13, 1847, Gen. Andres Pico, as newly appointed Commander-in-Chief of Mexican forces in California, met with Frémont at a Cahuenga Pass ranch house and formally signed the Articles of Capitulation.