-

- California and the Mexican War

- The Battle of San Pasqual

-

- Painting by Colonel

Charles Woodhouse, USMCR. Image courtesy of the Marine Corps

Recruit Depot Command Museum

-

-

- Probably the best known battle in California,

the Battle of San Pasqual is probably one on the most controversial

of the Mexican War. Debate rages to this day on who was the winner.

Did Kearney win since he held the field and could not be moved

off of Mule Hill until he was relieved the following day? Did

Pico win since his force remained a combat effective force even

after the battle? And if so, why didn't he follow up his earlier

success? By what standard do we judge? The contemporary standard

of the force that holds the field after the battle is considered

the winner? Or do we use the modern standard of the combat effectiveness

of the two forces during and after the battle?

-

- When considering these questions I am

reminded of a quote by historian David J. Weber of Southern Methodist

University:

-

- "Those of us who study history

for a living understand very well that there are many truths.

There are many valid points of view about a historical event…I

think it's better to think many truths constitute the past, rather

than to think of a single truth."

I am sure that this debate will continue for several years and

decades. But as it does, so will the discovery of our past.

-

- Dan Sebby, Sergeant Major

Historian

-

- The Battle

of San Pasqual

- By Geoffrey Regan

- Reprinted, with permission of

the author, from the book, SNAFU: Great American Military

Disasters.

-

- The Victor: Don Andres

Pico, circa 1846

-

As a substitute for rational thinking, some

commanders fall back on racial stereotypes by which they can assure

themselves that "man for man" their own soldiers are

in some way superior to the enemy. Such a man was Brigadier General

Stephen Watts Kearney, who, at the battle of San Pasqual, in 1846,

was guilty of such contempt for his Spanish-Californian opponents

that he suffered a sharp reverse-and still had the effrontery

to claim it as a victory and gain promotion for his "achievement"

With the outbreak of war with Mexico in

1846, U.S. President James K. Polk and Secretary of War William

Marcy decided to send Colonel Stephen W. Kearney, commander of

the 1st Dragoons at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas, to march into

New Mexico and to occupy Santa Fe. After seizing and garrisoning

New Mexico, Kearney, now promoted to Brigadier General, was ordered

to press on from Santa Fe with his "Army of the West"

deep into California, in order to seize Monterey and San Francisco.

Speed was of the essence as Polk wanted to ensure that if peace

came with Mexico the United States would have a military presence

in California sufficient to lay claim to that province.

The first part of his mission was accomplished

with ease, and Kearney occupied Santa Fe on August 18, setting

up a civilian government for New Mexico before pressing on into

California just four weeks later. With him now rode a mixed group

of civilians and soldiers: three hundred dragoons, a party of

engineers led by Lieutenant Emory with two small howitzers, and

hunters and guides under the experienced Antoine Robidoux and

Jean Charbonneau. Unfortunately the party was very poorly mounted

for the thousand-mile journey to the coast, many riding "devilish

poor" mules, some of which broke down less than a day out

of Santa Fe. With difficulty the party moved deeper into California

through desert country until, on October 6, they encountered a

group of riders who approached them yelling and whooping like

Indians. It turned out to be the legendary frontiersman Kit Carson,

with a nineteen-man escort, who was taking a message overland

to Washington from Commodore Stockton at San Diego. It seemed

that the struggle for California was over and that Stockton had

raised the American flag in the harbor at San Diego. With John

Charles Fremont already penciled in for governor, Kearney's "Army

of the West" was no longer needed.

Kearney sent back the bulk of his force

to Santa Fe and, keeping with him just 121 men and Kit Carson

as guide, he pressed on toward San Diego, sending ahead by the

hand of an Englishman named Stokes news that he had annexed New

Mexico and established a civilian government there. In his letter

to Stockton, Kearney asked for some well mounted volunteers as

an escort. Stockton reacted promptly, sending Lieutenant Archibald

Gillespie with a party of thirty-seven volunteer riflemen and

a field gun. Gillespie told Kearney about the state of the country

ahead and warned him that a band of insurgents led by Andres Pico

(younger brother of Mexican Governor Pio Pico) was no more than

six miles away at San Pasqual. In spite of torrential rain, which

had lowered morale in Kearney's party, the general could not resist

the opportunity of engaging the Californians. He called a council

of war and planned a reconnaissance of the enemy camp, prior to

an attack the following morning. A captain named Moore was loud

in his opposition to this plan, trying to convince Kearney that

he was underestimating the enemy, who were superb horsemen and

far too strong for the American troops on their feeble mounts.

It would be better to take the camp by surprise and strike the

Californians while they were dismounted. Once on their horses

the Californians would prove the masters. But Moore was overruled

and Kearney insisted on reconnoitering the Californian camp.

Gillespie offered the services of his "mountain

men" who could get in and out of the camp without arousing

suspicion, but Kearney insisted that the task should be carried

out by regulars, his aide-de-camp, Lieutenant Thomas Hammond,with

six dragoons and the Californian deserter named Rafael Machado.

This was a most unfortunate choice, as it turned out. Machado

led Hammond and his party into the valley of San Pasqual, to within

half a mile of an Indian camp. The deserter learned from the Indians

that Pico and his men, one hundred strong, were resting nearby,

completely unaware of the American presence. But Machado was taking

too long and Hammond's impatience got the better of him. He rode

into the Indian camp with his men, swords clanking, setting the

dogs barking. The commotion alerted the Californians, who leaped

up shouting, "Viva California, abajo los Americanos."

By sheer stupidity Hammond had blown Kearney's cover. As he and

his dragoons turned and rode for their lives, pursued by Californian

lancers, one of Pico's men found a blanket marked "U.S."

and a dragoon jacket dropped in the flight. Pico was now convinced

that Hammond's party was merely scouting for a much larger American

force. The Californians rounded up their horses and prepared to

abandon their camp.

Hammond returned to Kearney's camp to warn

him that Pico had broken cover and the general now decided on

an immediate attack, even though it was past midnight and the

weather was so cold that the bugler could not even sound reveille.

Some of the American troopers could hardly hold the reins of their

horses, which, with the mules, were in no better state themselves,

cold, sore and weak from lack of adequate fodder. Even worse,

nobody had seen fit to check the American firearms, which had

received a thorough drenching not long before. Unknown to Kearney,

he was leading a virtually unarmed force against an unexpectedly

dangerous enemy.

Once the Californians had been alerted and

surprise was lost, the Americans had little to gain by pursuing

them. Yet Kearney was able to convince himself that Pico was barring

the road to San Diego and therefore had to be driven off. In fact,

nothing could have been further from Pico's mind, which was concerned

simply with escape. It was merely the poor impression the American

soldiers made on him that tempted him to stand and fight Kearney,

aware of the deplorable state of his mules, was also keen to remount

his troopers by capturing some of the horses the Californians

had with them. But most telling of all was the impression given

to Kearney that the Californians were cowards and no match for

his men. How much this impression was gained from listening to

men like Kit Carson we cannot be sure, but what is certain is

that Kearney underestimated his enemy and failed to take precautions

before encountering him. Kit Carson had certainly told the general

that "all Americans had to do was to yell, make a rush and

the Californians would run away." Nor was Gillespie free

of blame, having expressed the view that "Californians of

Spanish blood have a holy horror of the American rifle."

In fact, Kearney may well have succumbed to the enthusiasm of

some of his men, bored after a long march and eager for action.

In any case, it was his decision to initiate the action and he

was to blame for what happened next In the words of one observer,

"Kearney, having made one of the longest marches in the history

of the United States, was spoiling for a fight and intended to

have it"

Kearney's men reached a ridge between Santa

Maria and San Pasqual still in good order, and it was here that

the general had his last opportunity to instill some discipline

into his force. Informing them how much their country expected

of them and encouraging them to charge with the point of the saber,

he gave orders to surround the Californian camp and take as many

men alive as possible. The column then began to descend the rocky

path into the valley, and soon became blanketed in low clouds

and fog. Confusion reigned. An order from the general to begin

to trot was misinterpreted by Captain Johnston's men at the front

and the captain suddenly drew his sword and shouted "Charge!",

even though he was more than a thousand yards from Pico's camp.

Kearney was heard to exclaim, "Oh heavens! I did not mean

that!" One of the camp followers later wrote in his private

journal what happened next:

Those which were passably mounted naturally

got ahead and they of course were mostly officers with the best

of the dragoons, corporals and sergeants, men who had taken most

care of their animals and very soon this advance guard to the

number of about forty got far ahead --- one and a half miles

at least-of the main body while the howitzer was drawn by wild

mules. In the gray of the morning the enemy was discovered keeping

ahead and with no intention of attacking but their superior horses

and horsemanship made it mere play to keep themselves where they

pleased. They also began to discover the miserable condition

of their foes, some on mules and some on lean and lame horses,

men and mules worn out by a long march with dead mules for subsistence.'

Instead of proceeding as a compact force

of riders, Kearney's men lost all cohesion and charged hell-for-leather

after the Californians. An advance guard of twelve dragoons under

Captain Johnston soon broke away from the men mounted on mules,

and with everyone riding madly forward on as unimpressive an

array of quadrupeds as ever graced the field of honor, it must

have resembled a gold rush rather than a cavalry charge. Behind

Johnston-a long way behind, as it transpired-rode Kearney, Lieutenant

Emory, and the engineer, William Warner, while behind them, laboring

along on mules exhausted by their thousand-mile journey, were

a further fifty dragoons. At the back, dragging the guns, came

Gillespie with his volunteers.

Captain Johnston rode straight into a party

of Pico's men who opened fire, killing him instantly. Seeing more

Americans approaching, the Californians rode off again as if in

retreat and Captain Moore ordered his men to continue their charge.

The chase lasted for another mile, until the American force was

stretched out down the valley. Suddenly the Californians wheeled

their horses around and charged the leading Americans, lances

at the ready. The shock of seeing their fleeing foe turn and confront

them made some of the Americans try to fire their rifles, only

to discover that their powder was so damp it would not ignite.

Thus disarmed, the dragoons were forced to resort to sabers and

rifle butts, which were no match for Pico's lances. Captain Moore

encountered Pico himself but his pistol misfired and before he

could strike with his saber he was speared sixteen times by lances

and fell dead from his saddle. The Americans were quite unaccustomed

to this kind of melee in which the advantage always rested with

the Californians' longer weapon. Almost every dragoon in the forward

party suffered from the points of the willow lances. Even more

surprising for the Americans, was the use made of the lasso, or

reata, which Pico's men cast with unerring accuracy, pulling the

dragoons from their horses and making them easy targets for the

lancers. Seeing Moore mortally wounded, his brother-in-law, Lieutenant

Hammond, rode to his side and died with him, pierced through and

through by the lancers.

By the time Kearney reached the scene of

the action, chaos reigned and he was unable to give any coherent

commands. It was every man for himself. Matters grew graver as

Kearney himself succumbed to a lance thrust in the back. Gillespie

and his mountain men were singled out by the Californians, who

bitterly hated them, and Gillespie himself suffered numerous wounds,

including a lance thrust over the heart. Crippled but undaunted,

Gillespie fought his way back to the artillery pieces, which had

by now arrived, and brought one into action with the help of a

naval midshipman, James Duncan. The Californians, dragging off

one of the guns, now broke off the engagement and rode away down

the valley. It had been a brief encounter, possibly lasting less

than fifteen minutes, but American casualties had been very severe.

No more than fifty of the Americans had come into action, but

of these twenty-one died and seventeen were seriously wounded.

Losses among the officers and NCOs were particularly severe: Captains

Johnston and Moore, Lieutenant Hammond, two sergeants and a corporal

were all killed by lance thrusts. General Kearney and Captains

Warner, Gillespie and Gibson were all seriously wounded, along

with Antoine Robidoux.

It had been a thoroughly bad battle from

the American point of view. It has been claimed in Kearney's defense

that because Pico abandoned the field the Americans were thereby

victorious, but it is a ridiculous assertion. Pico had never intended

to fight; his only concern was to escape from his pursuers. In

his own words he "could not resist the temptation" to

attack the Americans because their pursuit was so disorderly and

their appearance, on mules, aroused the contempt of his followers,

men born to the saddle. Kearney had seriously underestimated his

opponents, always a serious mistake in a commander, and knew little

of their technique of fighting. His advantage rested in the training

of his professional troops and in his own appreciation of the

military art. It did not consist in chasing thoroughbred horses

on blown mules, or matching damp powder and sabers against lassos

and lances. Gillespie should have been able to tell him something

about the way the Californians fought, but it is clear that Kearney

was not in a hurry to listen. Dr. John S. Griffin, who was present

at the battle, mournfully commented, "This was an action

where decidedly more courage than conduct was shown." One

of Moore's dragoons put it more pointedly: "such another

fight was unknown-it was a disgrace" while a number of his

men felt that it would have been no more than he deserved had

the general died of his wounds. Had he waited for daylight, they

suggested, there would have been far fewer casualties. Kearney

blithely reported the battle as a victory, "but (we) paid

most dearly for it"

Kearney's performance at San Pasqual earned

him promotion, but might instead have won him a court-martial

for incompetence. In almost every way his leadership was at fault.

The bloody skirmish at San Pasqual was an unnecessary battle,

fought to satisfy a general's ego and to indulge the jaded appetites

of a group of adventurers masquerading as soldiers. As a professional

soldier himself, Kearney made almost every mistake in the book.

When Pico's camp was discovered, he ignored Gillespie's offer

of help and allowed the blundering Hammond to alert the Californians

to his presence. He took up the challenge of pursuing an enemy

of unknown numbers and firepower by night and with a force inadequately

mounted and with rifles soaked by torrential rain. Even though

an alternative route to San Diego was available, he claimed that

Pico was barring his route to the coast and had to be challenged.

Having conceded advantages in mobility and firepower to the enemy,

Kearney also prepared to fight them on unknown terrain and in

such poor visibility-from darkness and mist that his own men had

great difficulty in telling friend from foe. But above all, and

this is unforgivable in any commander, he allowed the prejudices

of others (notably Kit Carson) to persuade him that his enemy

was unworthy of respect. Underestimating the qualities of the

Californians, notably in their horsemanship and in the superiority

of the lance and lasso in close-quarter fighting, he allowed his

force to rush blindly to destruction. Once in action Kearney failed

to impose himself on his men and allowed Johnston's erroneous

order to disrupt the actions of the entire force. A swift countermand

might have brought up even the advance guard in its tracks. Better

by far to allow the Californians to escape than to allow his own

force to be cut up piecemeal.

With General Kearney incapacitated, Captain

Turner, the ranking officer, sent an urgent message to Stockton

at San Diego asking for help, but before the news of the disaster

reached Stockton, the "Army of the West" had clashed

again with Pico's force near Rancho San Bernardo. Kearney's force

was now surrounded by the Californians, who obviously hoped to

starve them into surrender. Fortunately, within two days, Stockton's

relief force of one hundred sailors and eighty marines led by

Lieutenant Gray of the U.S.S. Congress raised the siege and escorted

the exhausted survivors of Kearney's "army" into San

Diego. Kearney's march from Fort Leavenworth had been a triumph

of exploration and endeavor, and the general had shown astuteness

in dealing with his civil duties in establishing a government

in New Mexico. Unfortunately, it was as a military commander that

he failed both himself and his men in the wholly unnecessary battle

at San Pasqual.

- The vanquished. Brigadier

General Steven Watt Kearny

-

- Other Accounts

of the Battle

-

- Pro-American commentators such as these

were quick to claim victory in this short battle with Californios,

but the truth is that the day belonged to the troops of Andres

Pico. Pico, whose troops were outnumbered and outequipped by

the Americans, pretended to retreat. As the Americans pursued,

the Californios suddenly turned and charged with their lances

against the Americans' guns. The tactic so surprised Kearny's

troops (exhausted by a transcontinental journey) that they were

forced to take up a defensive position atop a nearby mountain

until relief arrived from San Diego the following day.

-

-

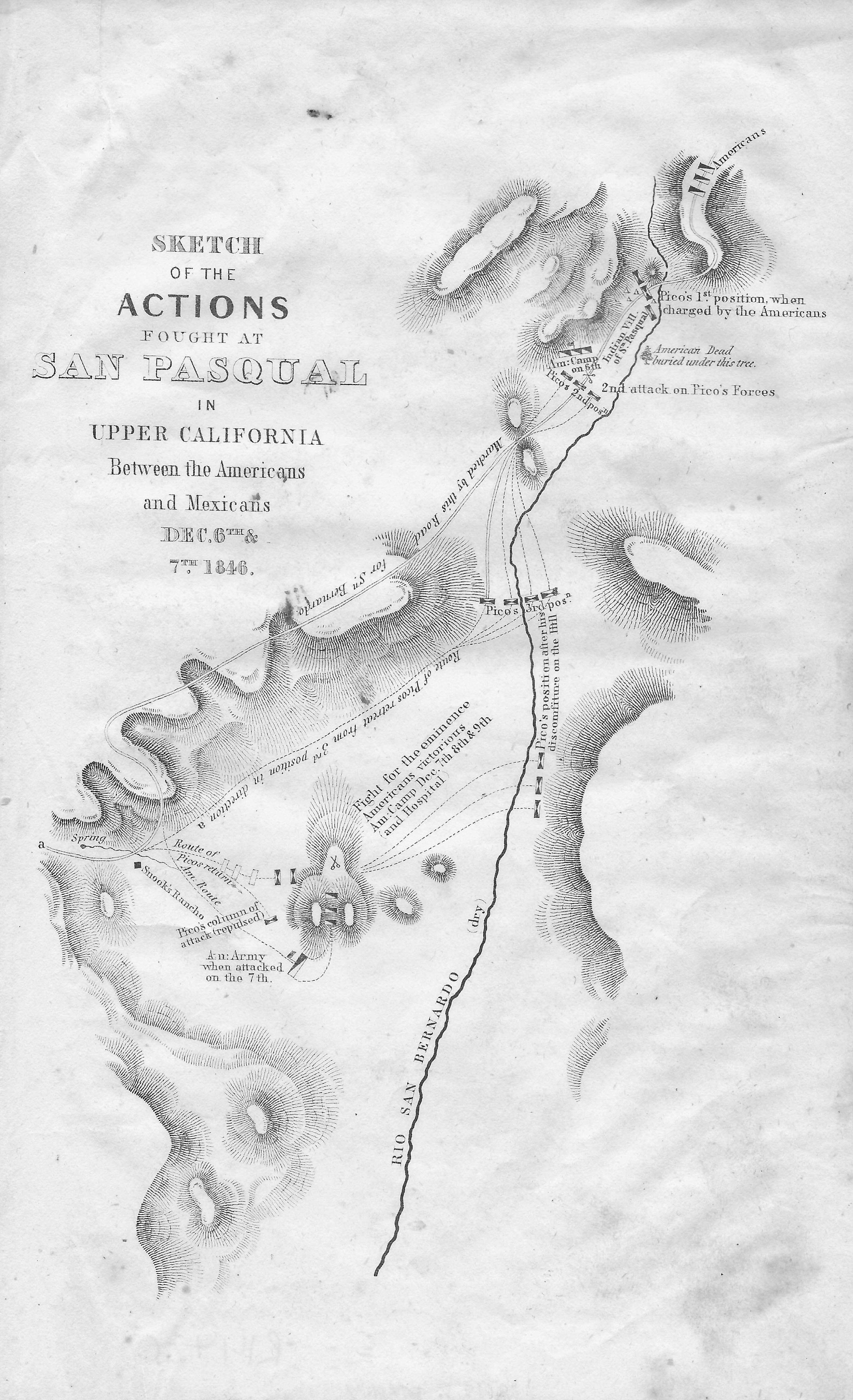

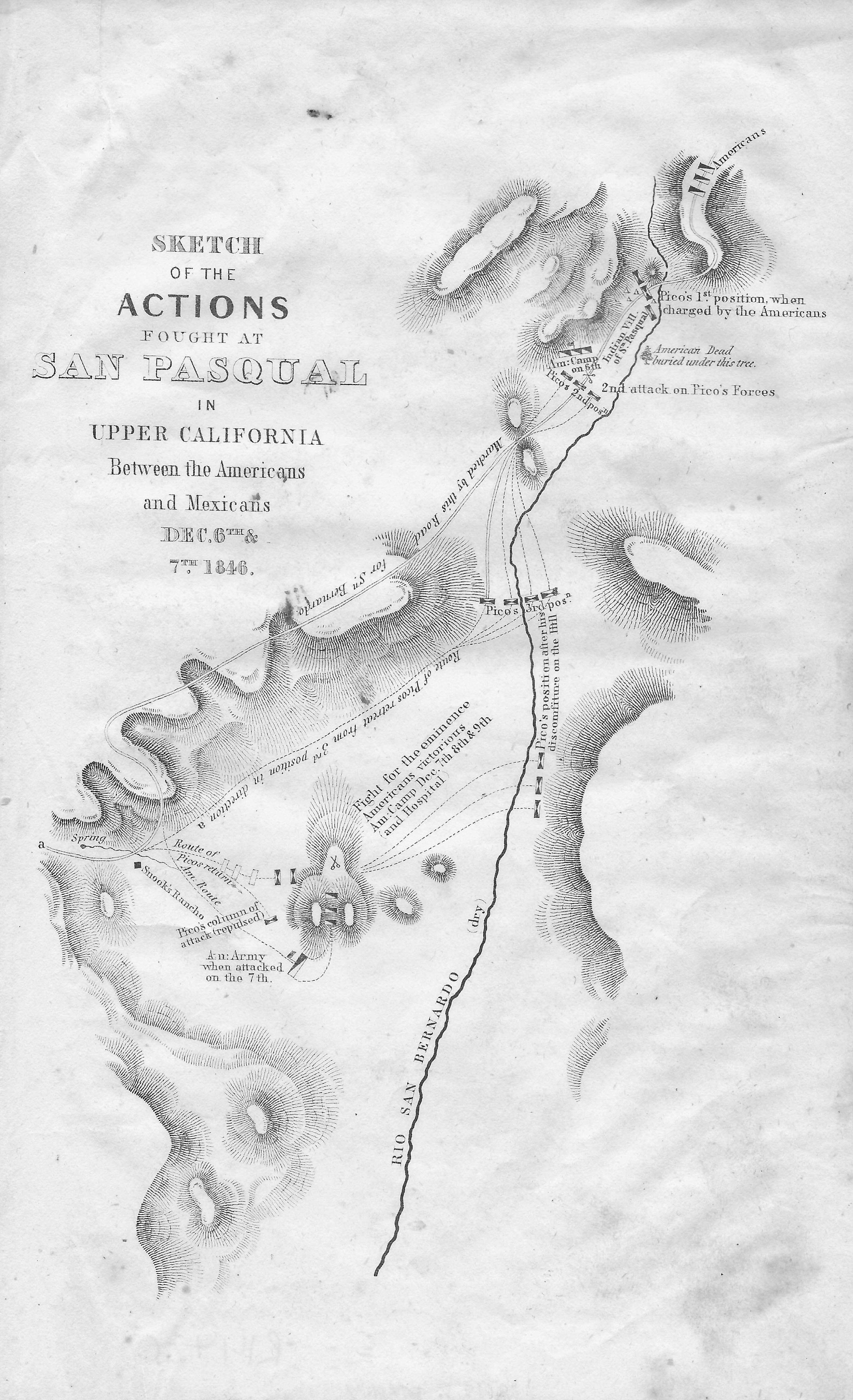

- Contemporary

map of the Battle of San Pasqual. California Military Department

Historical Collection. Click Image for a larger view.

-

-

- From A Gil Blas in California,

by Alexandre Dumas (1852)

-

- In the meanwhile, after enduring

unbelievable fatigue and suffering time and again for the lack

of prime essentials, Colonel Kearny, with his 100 men, marched

over the Rocky Mountains, crossed the sandy plains of the Navajo

Indians, passed the Colorado, , after traveling through the lands

of the Mohave Yuma Indians finally reached Agua Caliente.

-

- Upon arriving he fell in with

a small troop of Americans, commanded by Captain Gillespie, who

told him definitely what was taking place in California and warned

him that ahead of him was a troop of seven or eight hundred men

commanded by General Andres Pico, who was in control of the country.

Colonel Kearny counted his men. There were only 180 all told,

but they were resolute and well-disciplined soldiers. He then

gave the order to march on the enemy. Americans and Californians

clashed on December sixth out on the plain of San Pasqual.

-

- The engagement was terrific;

for a time the small American forces were defeated and nearly

routed. Ultimately, however, they were victorious. Colonel Kearny,

who from then on was made general, received two wounds, and had

two captains, one lieutenant, two sergeants, two corporals, and

ten dragoons killed. The Californians, on the other hand, lost

two or three hundred soldiers. [This is exaggerated. The losses

of the Californians were probably slight.]

The following day, a detachment of marines sent by Commodore

Stockton joined Kearny whom they had been sent out to meet. Thus

reinforced they continued to march on toward the north. On December

eighth and ninth, he had two more clashes with the Californians

but in these engagements, as in the first battle, he emerged

victorious. At the same time Castro, now a fugitive, encountered

Captain Fremont, and after being surrounded by him, capitulated.

A few Californian troops still remained in the vicinity of Los

Angeles.

-

- From Seventy-five years

in California; a history of events and life in California: personal,

political and military; under the Mexican regime; during the

quasi-military government of the territory by the United States,

and after the admission of the state to the union: being a compilation

by a witness of the events described; a reissue and enlarged

illustrated edition of "Sixty years in California",

to which much new matter by its author has been added which he

contemplated publishing under the present title at the time of

his death; edited and with an historical foreward and index by

Douglas S. Watson--by William Heath Davis (1929)

-

- Lieutenant Beale was sent out by the

commodore to meet Kearny and guide him to San Diego. On reaching

San Pasqual , at which place Kearny had then arrived, Beale found

that the general had from I 20 to 130 men with him, all suffering

severely from cold and lack of food. The winter was an unusually

severe one, snow and frost prevailing, which was very seldom

known in that latitude, and the men had experienced many hardships

on the way from New Mexico to this point. They had no horses,

only mules. Lieutenant Beale informed General Kearny that he

had been sent by the commodore as a guide, and that it would

be advisable to avoid meeting Don Andres Pico and his force of

cavalry, consisting of about 90 men, who were then in the vicinity

of San Diego, having been dispatched from the main body of Californians

near Los Angeles for the purpose of watching Stockton's movements

and preparations, and communicating information of the same to

headquarters. Commodore Stockton, knowing of Pico's presence

in the neighborhood, and that he had a well-mounted force, in

fine condition, thought it best for Kearny's troops not to meet

them, probably surmising that the latter were not in very good

fighting condition, after their long march during the cold weather;

or, probably, he had been informed of this by Captain Snook.

Upon Lieutenant Beale's communicating Commodore Stockton's views

to Kearny, the latter promptly responded, "No, sir; I will

go and fight them," and declined to act upon the suggestion

of the commodore.

-

- Beale had observed the starved appearance

of the men and their bad circumstances generally. He intimated

to Kearny that as they were worn out with their recent march

and had not found time to recruit, they were hardly in a fit

condition to meet the Californians, who were numerous, as well

as brave, and not to be despised as enemies. He also represented

that the mules would be no match for the horses in a battle,

even if in the best condition. Kearny declined to be influenced

by the argument, being determined to have a fight. He was saved

the necessity c.f moving to meet the Californians, however, for

the latter having learned of Kearny's force at San Pasqual ,

shortly appeared there, and, led by Don Andres Pico, made an

attack upon the 6th of December.

-

- When the Californians observed the

appearance of Kearny's men, and how they were mounted, they remarked

to each other, " Aqui vamos hacer matanza ." ("Here

we are going to have a slaughter.") They were mounted on

fresh horses, and were armed with sharp-pointed lances and with

pistols, in the use of which weapons they were very expert. A

furious charge was made upon Kearny's force, whereupon all the

mules ran away as fast as their legs would convey them, pursued

by the Californians, who used their lances with great effect,

killing about twenty-five of Kearny's men and wounding a large

number (including General Kearny) of the remainder (nearly all

of them in the back), who were all in the predicament of being

unable to control the half-starved mules which they rode at the

time of the stampede. The general, however, managed to rally

his men and the mules, and, taking a position, held it against

the attacking forces, who were not able to dislodge him. The

Californians withdrawing from the immediate scene of action,

Kearny buried his dead, while expecting that at any moment the

enemy would renew the fight.

-

- In this conflict Beale was slightly

wounded in the head. At his suggestion Kearny moved his force

to the top of Escondido mountain, which lay in the direction

of San Diego, marching in solid form, so as to be able the better

to resist any attack that might be made, the mountain offering

advantages for defence which could not be procured below. While

there encamped they were surrounded and besieged by Pico and

his troops who made another attack, but without success.

-

- In the battle just described, Don Andres

Pico, who was brave and honorable, displayed so much courage

and coolness as to excite the admiration of the Americans. He

never did an act beneath the dignity of an officer or contrary

to the rules of war, and was humane and generous. If he saw one

of the enemy wounded, he instantly called upon his men to spare

the life of the wounded soldier. Kind and hospitable, Pico was

held in great esteem by the Americans who knew him.

-

- While Kearny was thus besieged, Lieutenant

Beale volunteered to make his way through the enemy's lines and

communicate to Stockton the intelligence of the general's position

and circumstances. It was an act of great daring; but by traveling

in the night only, and part of the time crawling on his hands

and knees, to avoid discovery, he finally reached San Diego,

nearly dead from exhaustion, his hands and limbs badly scored.

-

- When he came into San Diego he was

little more than a skeleton; his friends hardly knew him. He

gave an account of what had transpired and of the condition of

Kearny's force. As soon as his mind was relieved of the message

he became utterly prostrated from the sufferings he had undergone,

and shortly after was delirious. It was some time before he recovered.

Stockton and the other officers of the squadron showed him every

attention.

-

- A force of two hundred men, with some

light artillery, was immediately sent to rescue Kearny's troops

and escort them to San Diego, also conveyances for the wounded,

with full supplies of provisions. The Californians moved back

as this force approached, not venturing further demonstrations.

The troops, with the wounded, were brought to San Diego.

-

-

- Search

our Site!

-

-

Questions and comments concerning

this site should be directed to the Webmaster

-

Updated 20 January 2019